The Dacian Dragon Standard in England00:59 Feb 09 2014

Times Read: 712

The Dacian Dragon Standard in England

THE DACIAN DRAGON STANDARD, KING DECEBAL,EMPEROR TRAJAN AND KING ARTHUR

by Andrei Dorian Gheorghe & Alastair McBeath,

first published in The Dragon Chronicle, Number 12, April 1998

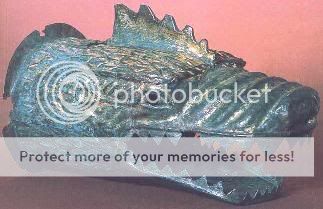

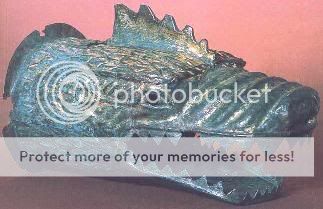

Head of parade Dacian draco (Vienna exhibition)

The Dacian battle standard was a dragon, made up of a metallic wolf’s head with a serpentine cloth body, a little like an aerodrome windsock, and through which

the wind would hiss and howl, making a particularly terrifying impact on any enemies.Similar standards were used by the Indians, Parthians, Persians and Scythians,but where the original idea came from is unknown, perhaps from contact with peoples of China and Mesopotamia, where flying dragons were long-established mythical creatures.

Such dragon standards appear both in archaeological evidence, including Trajan’s Column, and also in written material of Roman origin. The Romans fought major conflicts against both the Dacians and Parthians under Trajan’s rule, both of whom used this dragon as a battle-flag, but it is clear from what we have seen already that Trajan’s most major efforts were made against, and his most important victory was over, the Dacians.

However, we do not definitely know whether it was these conflicts, or the recruitment

of auxiliary troops from Dacia, Sarmatia or Parthia, or indeed a combination of all,

which finally brought about the general adoption of the draco standard of this animal-head-and-cloth-cone type as the emblem of the cohorts throughout the entire Roman army during the 2nd century CE.

There is some evidence to suggest the Germanic tribes also used dragon standards of similar types, although whether these were adopted after contact with the Roman versions is less clear.

Certainly the Continental Saxons of the post-Roman period seem to have used such battle emblems, but their origins are difficult to ascertain in the absence of written records.

They do at least appear to have been used at a later period than those of the Dacians/Parthians/Sarmatians and their Roman masters (cf. Heath 1980; Lofmark 1995).

This is not to say that the dragon was unknown to these people, and others,both at this time and much earlier, since there is strong evidence to support dragons as symbols used on coins, armour and jewellery, amongst other things,from a far earlier time than that of the Roman cohort dragon standards (Lofmark 1995) contains a good, brief introduction to this broad subject.

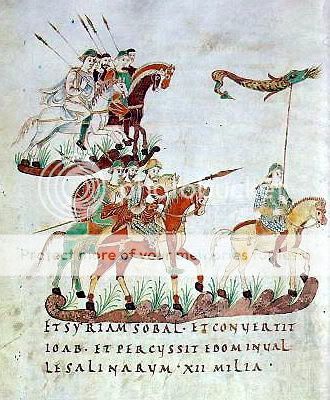

The widespread use of the dragon standard in the Roman army would have brought it to Britain in a short time, and as it was only in 407 CE that the last Roman troops were withdrawn from Britain, for around 200 years,the British population would have been used to being guarded by forces led by dragon emblems.

After the Romans departed, it would probably have seemed quite natural to the Romano-British people to retain the dragon standard for their own troops,and written evidence from the late 6th century (as well as less reliable earlier sources)indicates the term “dragon” was widely used to signify a leader.

Thus although Geoffrey of Monmouth may indeed have almost single-handedly “invented” Arthur in the form so successfully taken up and perpetuated by later medieval writers (such as Thomas Malory), enough historical evidence is available to suggest that a leader of “Decebalian” stature did indeed exist in Britain, and that he would have been associated with the dragon standard,as well as very probably being called something like “pen-dragon” or chief dragon (Ashe 1990; Lofmark 1995; Nicolle 1984).

Consequently, we have the fascinating prospect that the “Romanian Arthur” King Decebal may have helped create the British Arthur,and more likely helped transfer the battle-flag dragon across Europe to Britain in the early centuries CE.

One further point is that as British auxiliary troops served with the Romans in the Dacian campaigns, and Dacian auxiliaries later served with the Roman army in Britain, such a transfer of the dragon-standard might have seemed even more natural.

Other auxiliaries came from all over the Empire, and either this,or the Dacian’s Germanic allies the Bastarnae might have helped spread the standard to the Saxons, as well as Roman influence. After the Arthurian period, the dragon remained in use as a British standard

for warriors, or at least their leaders, until 1066, with frequent battles throughout this period between the dragons of Britain and those attempting to invade from overseas - e.g. the Danes and Saxons.

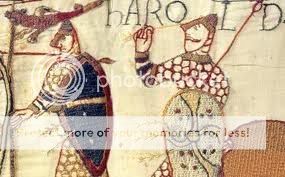

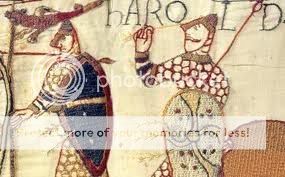

Bayeux Tapestry with a draco standard

The Bayeux Tapestry shows one of the last representations of the British battle dragon

in its earlier form, where two are depicted, one already fallen with its bearer beside

the famous figure with an arrow in his eye, who may or may not be meant to represent King Harold himself(e.g. Stenton 1965, especially plate 71 and pp.187-188).

The two standards certainly seem to imply the last stand of the King’s household troops, and it is even possible that the fallen dragon standard itself may be intended to show Harold’s death, rather than the figure with the arrow impaled in him.

The invading Normans, although they clearly made use of coiling serpentine dragons

as designs on their shields, do not appear to have used dragon standards at all,and it is not until Richard I used one in 1190 at Messina that we find a Norman king in association with a dragon battle standard (Lofmark 1995).

As we know, dragons refuse to go away permanently, and although various monarchs since have used or ignored the dragon standard in Britain at their whim (or as political necessity dictated), the dragon still persists as animportant symbol at many different levels in modern Britain.

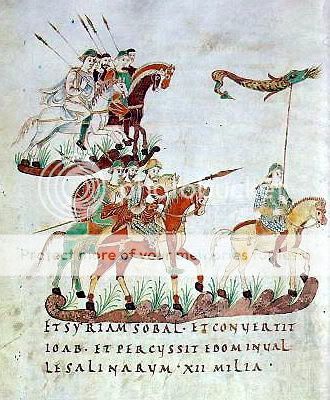

Carolingian cavalrymen from the 9th century with a draco standard

COMMENTS

-

Isis101

02:59 Feb 09 2014

This was very interesting and informative. Thanks!

Dragonrouge

09:48 Feb 19 2014

My pleasure! It seems like an interesting hypothesis that deserves to be researched!